Teachers influence people’s lives. There is no doubt that education systems globally are striving to improve how teachers teach, especially given the potential for teachers to influence improvements in learner outcomes (Timperley, 2012). We know that there are a number of moving parts that shape how schools, networks and education systems manage improvements to teaching and the consequent improvements to learning. These include school norms and values, policies, and funding for resources and professional learning.

However, I want to draw attention to the importance of high-quality professional development for teachers

Recently, the New Zealand Ministry of Education has undertaken a mammoth revision of the formalised school curriculum, which is still ongoing. Alongside this, they have revised the national professional learning priorities based on student achievement data for core learning outcomes and progressions in literacy and numeracy. The priorities for 2025 are: structured literacy, mathematics and assessment. The Ministry of Education are currently promoting and encouraging all primary teachers to participate in professional learning associated with these priorities. Associated with these shifts in priorities for schooling improvement, there is a need to re-examine the best way to implement professional development for teachers. This is because teachers are incredibly busy and there is limited time and energy in schools. Improving teaching requires professional learning to be focussed specifically on what needs to be improved, not just because it represents better value for money, but that it is too important to get wrong or just to be mediocre.

Quality professional learning

As Timperley (2012) implies, professional learning needs to be of high quality, in that it is effective, manageable and sustainable. Effectiveness is often measure by reach and impact. Reach data, i.e. how many teachers have participated in the PLD, is a way of indicating the PLD was delivered. Impact is more difficult to measure because it can relate to a combination of teachers’ self-reports, peer observations, student perceptions and student outcomes. Improved student outcomes are the end game. Measuring changes in student outcomes is therefore a good proxy for impact. I use proxy because there are a multitude of other factors, such as student attendance, that can influence outcomes that are not necessarily directly related to Professional learning.

One way of ensuring there is equity in quality of delivery for specific PLD for teachers is to centralise planning and development of professional learning opportunities. The Ministry is applying this to the mathematics curriculum PLD, where the same workshops are delivered nationally. While this is very useful to provide a consistent message and convey information, it doesn’t necessarily address the specific needs within specific learning environments or contexts that present challenges because of their unique situations. It’s important for teachers to be aware of changes but then they need to apply the changes in focus in practice. Therefore, combining this valuable learning with more detailed in-school professional development, can support teachers to apply what they learn directly to improvements in teaching. Cognition Education are very pleased to be the national provider for in-school professional learning for accelerating learning in mathematics.

The Ministry are also ensuring a quality gate for Ministry-funded facilitators of professional learning by selecting only those with specific skills to implement specific opportunities. Facilitators of Ministry funded structured literacy are required to have received Ministry accreditation, where qualifications and professional learning associated with structured literacy must be demonstrated.

As well, the extent of influence or impact that PLD has on student outcomes will depend on:

- alignment with a theory of improvement

- anticipated changes that are specific

- monitoring that the activities are happening and

- evaluation about the extent that the changes have led to the desired future state. (Hamilton and Hattie, 2022)

Quality can also be assured through starting with what’s going to make the most difference and building in monitoring and evaluation of the desired actions and outcomes with iterative changes that are based on deep inquiry and reflection.

Schools also have their own improvement plans, often with a clear focus and direction, including how they will implement professional learning. During times of change, it’s worth reconsidering exactly what’s most important to focus on for the most effective actions to reach the desired outcomes. Bringing government and school agendas together may require concerted efforts to carefully craft more specific school improvement plans.

Developing a school improvement plan

Successful improvement of learners’ outcomes is more likely when professional learning activities align with the school strategy focussed on improvement (Robinson et al., 2017) using a working theory of improvement. This is because it’s important to ensure that the opportunities for teachers to learn are focussed, based on “data” and are relevant to the learners they support in their local context. What may be appropriate in one context, may not necessarily relate to the specific areas needing to be addressed in another. That is, learners have differing needs, they are supported by different teachers who bring variable skills and experiences and the learning environments may need to be modified differentially depending on specific needs. This means rolling out resource-based interventions, as if they will provide the desired effects on improvement is not by itself, going to lead to the improvements required (Katz, et al. 2009). Rather it is a combination of planning and implementing support for teachers to understand how to use and apply teaching approaches that align with school improvement plans, that make the biggest difference (Hattie, 2012).

In our experience of working with hundreds of schools, we find that increasingly it is those leaders who are open to and seek support for designing and implementing these processes, (with their staff, boards and external facilitators), who gain traction on the desired improvements. The whole school improvement process is enhanced when deep inquiry and specific data sets are used to help drive decisions. Please see Data Led School Success for how this opportunity can help you to refine your school plans.

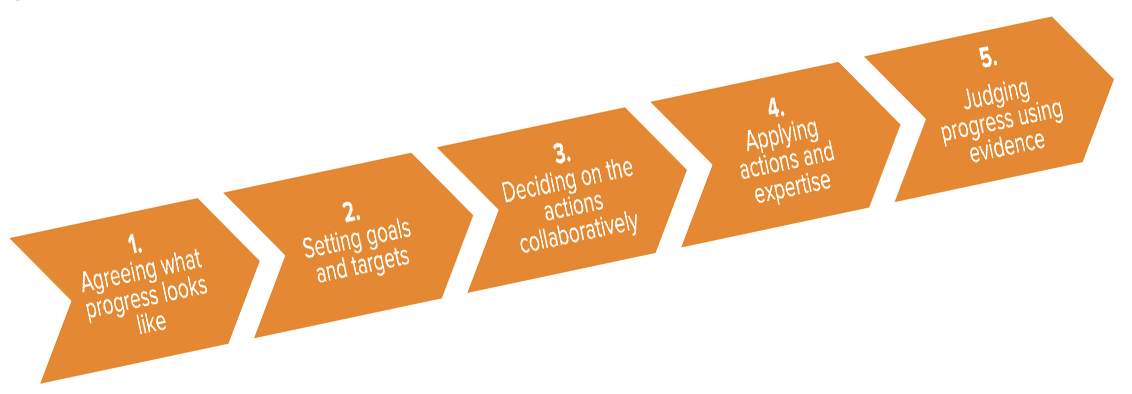

The sequence of developing and implementing the phases and actions of school plans can be represented by these stages which link to each other and can iterate back and forth.

Cognition Education look forward to providing schools and teachers with quality professional learning to help you achieve or exceed your schools’ desired learning improvements, but this requires sharing achievement information so we can evaluate the impact. After all, we all want to know how effective we’ve been and how data might inform us about the next steps for continued improvement.

References

Hamilton, A. & Hattie, J. (2022). The lean education manifesto. Routledge

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: maximizing impact on learning. Routledge.

Robinson, V., Bendikson, L., McNaughton, S., Wilson, A., & Zhu, T. (2017). Joining the dots: The challenge of creating coherent school improvement. Teachers College Record, 119, 1-14.

Timperley, H. (2012). Realising the power of professional learning. Open University Press.

Timperley, H., Ell, F., Le Fevre, D. & Twyford. K. (2020). Leading professional learning: practical strategies for impact in schools. ACER Press.