Written by Rebecca Thomas and Steve Saville.

The start of a new year; a new cohort of learners, the return of an energised staff and a new set of goals await. Educators continue to seek ways to make changes to their education systems, vowing not to just return to the status quo. Collectively leaders are determined to learn from experience and reflection and use the knowledge gained to implement changes that will enhance learner agency, personalised learning and intrinsic motivation.

The following texts may help create an insight into the change process ahead:

- Te Hurihanganui

- “Navigating the Stars” by Witi Ihimaera

- “Teaching to the North East” by Russell Bishop

Relationships are placed firmly at the centre and they also use the idea of ‘creation’ (starting at the beginning) to drive their messages home. But most importantly they alert us to the necessity for leaders to engage with ākonga, hapū, iwi and Māori communities, from a Māori cultural framework, to begin to address racism and inequity.

Outlined below are summaries from these important texts that could give your leadership team some grounding and possibly some guidance on how to support critical change for the year ahead.

Te Hurihanganui

Te Ao Māori – Rich and legitimate knowledge is located within a Māori worldview. To honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the education system must create and hold safe spaces for this knowledge to thrive, supporting Māori to live and learn as Māori.

People’s perspectives are culturally framed and grounded in everyone’s own individual values. This is one reason that different people might interpret the same situation in different ways. When faced with a challenge we may look at problems from our own perspective using the same filters and approaches that we have always used, thus creating outcomes also likely to be the same as they have always been. Changing our perspective and looking at issues using a different lens may possibly facilitate a different outcome.

This diagram from Hurihanganui highlights the process of change but presented from the view of the Māori explanation of the creation – let’s start at the beginning.

The initial stage of uncertainty and unease with the status quo is presented as Te Po; the darkness. The next stage is Te Wehenga; the plan for action. This is followed by Te Ao Marama; the change, the light. This is presented as a painful stage with ongoing implications and therefore needs the final stage Te Hurihanganui; the act of love to ease the pain. The change process outlined in the model highlights the need for us to collectively address racism and inequity in the system.

Placing the change process firmly in Te Ao Māori; the concept of moving from darkness to light, the fact that the change is painful and, most importantly, the need for redemptive love to heal the wounds all provide a different hue to the change process, perhaps allowing an old problem to be approached in a slightly different way.

Repositioning ourselves before we engage is also something Russell Bishop et al. fondly highlights to us in Bishop, Russell & Berryman, Mere & Richardson, C.. (2003). Te Kötahitanga: The Experiences of Year 9 and 10 Mäori Students in Mainstream Classrooms. Critical consciousness is the ability to recognize and analyze systems of inequality and the commitment to take action against these systems. Raising levels of critical consciousness can help create a gateway to academic motivation and achievement for marginalized students by ensuring their environment and interactions are culturally responsive. Combined with Kaupapa Māori these two drivers might enable us to challenge ourselves in the coming year, thus allowing opportunities for transformative changes in practice. Next time you think about changing something in your school, ask yourself what the change looks like for everyone involved.

Before you step foot on your journey be sure you know the stars.

Navigating the Stars

Once a shared goal is realised from a unified perspective, hope and understanding can be the building blocks to collaborative relationships. Shared aspirations help us to visualise the journey ahead and enable us to align to our goals.

In the introduction to ‘Navigating the Stars’ (a book that blends fact, fiction and philosophy captured in Māori whakapapa pūrākau), Witi Ihimaera highlights the importance of how stories have been central to our human history and they have helped shape who we are. Each storyteller might tell a slightly different version of the same story; perhaps using different words, but the main key messages stay the same. When we look at myths they also invite us to reflect on possibilities. We might begin to ask ourselves, ‘What if’ – beginning the provocation of truly aspirational goals.

Lastly, just as a storyteller shares their understanding of the world, the words they choose to use can create a shared understanding for the audience – in turn helping us to make connections and giving us a sense of belonging.

Teaching to the North East

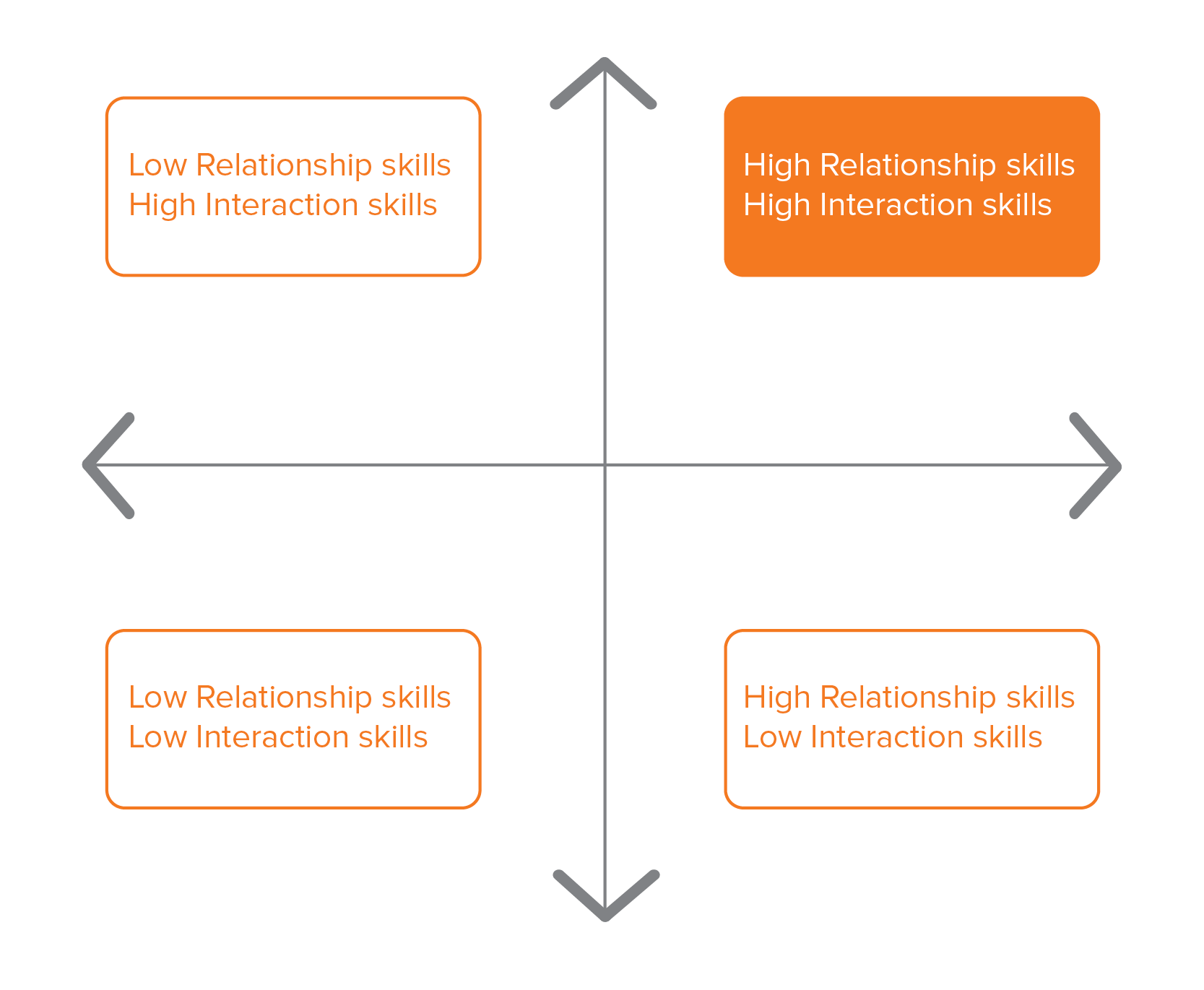

Being able to find the courage to develop a leadership style where relationships thrive means we need to engage with each other on a level of high trust – culture truly does matter. When we have this ‘trust’ leaders can build learning communities that thrive. Russell Bishop’s concept of aiming to teach to the North East [see diagram below] holds relationships firmly as the first thing we need to get right. The quadrant where we are aiming for is where there are both high relationship skills and high interaction skills. Where a whānau-like extended family environment nurtures and cares for the students within it.

Bishop clearly articulates that it is one thing to move into this quadrant but quite another to stay there. Sustaining change means that we have to continuously monitor ourselves and our relationships with the whole community; creating the need for leaders to collect as much data as possible to ensure actions remain impactful. Russell Bishop has discussed this in more detail in a recent blog, here.

We gather data all the time; what we find depends largely on how we gather this data and the questions we ask, which in turn influence our conclusions and actions. A mixture of quantifiable data and personal voice will give us a more accurate picture of progress, helping us to change and modify our leadership skills so we can remain in the North East.

Personal voice is likely to be more effectively presented as narratives, rather than a series of graphs. Data at a quick glance on a graph can be impactful, but as Witi Ihimaera reminds us, the story is at the heart of its creation; be mindful that we don’t allow the graphs to depersonalise the journey.

Change is an opportunity to do something amazing

Maintaining representative perspectives, shared narratives and family-like relationships at the heart of any change initiative might serve you well as you begin the journey ahead. Make 2021 a productive and thought provoking year for education.